Software bills of materials (SBOMs) provide a list of the components, libraries, and modules that are required to build a piece of software. The United States 2021 Executive Order on Cybersecurity highlights the role of SBOMs in supporting risk assessments for newly discovered vulnerabilities. Further, the U.S. National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) released its Secure Software Development Framework, which requires SBOM information to be available for software. Both open-source and commercial software are impacted by these policies. Consequently, developers of scientific software should expect that the use of their software may be restricted in some contexts unless accurate SBOMs can be generated. Conversely, as SBOMs become more widely available for scientific software, developers will also be able to use them to better understand the risks and vulnerabilities of the software on which they depend.

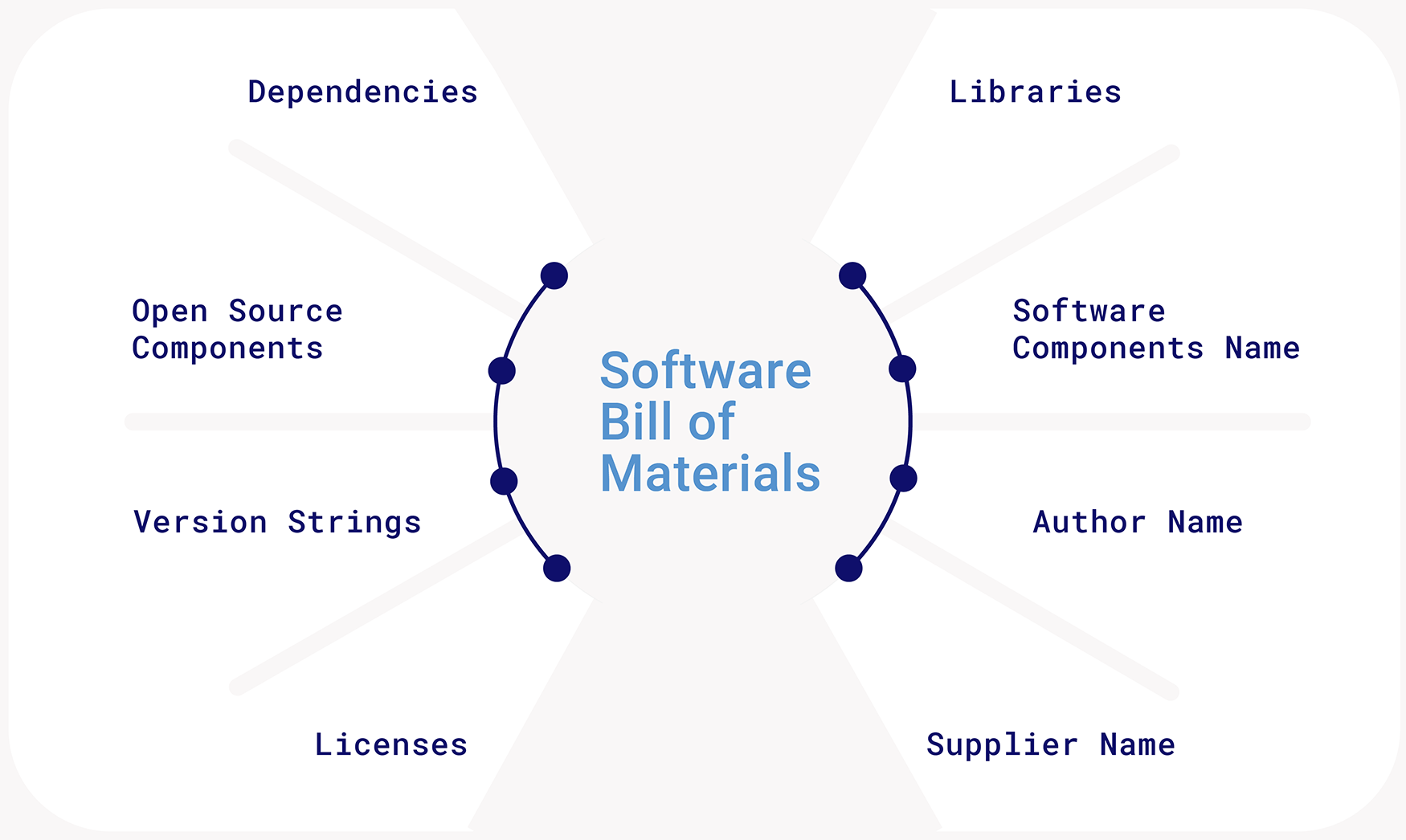

Ingredients of a software bill of materials.

Ingredients of a software bill of materials.

The past few years have seen an industry-wide effort to embrace SBOMs and other software security practices highlighted by the U.S. government (see, for example, this article). Many tools have been developed to generate SBOMs for software repositories, filesystems, container images and other execution platforms. The software bill of materials webpage maintained by the National Telecommunications and Information Administration provides an extensive set of resources on their creation and use, including the Survey of Existing SBOM Formats and Standards (2021), which describes the three widely used SBOM standards that have emerged. Although SBOMs and other software security practices are not yet widely used in the scientific software community, policies for software security will increasingly impact scientific software too. Consequently, developers of scientific software should begin learning about SBOMs and their role in software security best practices, and scientific software developers should assess how to provide and use SBOMs in their own development activities.

In recent blog posts, I provide a critique of these capabilities in the context of scientific software libraries written in Python and C++. Specifically, I explored whether mature tools exist to automate the generation of SBOMs for scientific software. Many of the tools discussed in the blog concerning SBOMs for C++ can be used with other compiled scientific software languages, including Fortran and C.

Here is a synopsis of the key points from these blogs:

Existing tools can easily generate SBOMs for simple Python packages. Simple Python packages without C extensions probably do not need to worry much about generating SBOMs.

-

Developers should be clear about the distinction between required and optional dependencies.

- Optional dependencies may not be captured in SBOMs.

- Further, optional dependencies may be treated differently in different SBOM tools.

-

It is unclear how to capture build dependencies in SBOMs for cython and other compiled software extensions.

- Compiled dependencies are employed in widely used Python libraries (e.g., numpy).

- However, the SBOM tools I surveyed for Python focused on documenting software dependencies but not software builds.

The SBOM tool ecosystem is much less mature for C++, Fortran, and other compiled languages used for scientific computing.

-

C++ and Fortran developers should explore the use of package managers.

- These naturally manage the relevant SBOM data, so package managers will likely play a key role in supporting software security practices.

- However, only a couple of package managers currently automate the generation of SBOMs: vcpkg, Conan and Spack.

- Of these, vcpkg currently has the strongest support for SBOMs (e.g., see this Microsoft blog article).

-

Alternatively, C++ and Fortran developers can automate the generation of SBOMs within their build systems.

- For example, the cmake-sbom project automates SBOM generation with build information the developer provides.

Further information

- SBOMs for Scientific Software: Python

- SBOMs for Scientific Software: C++

- NTIA Software Bill of Materials

- United States Executive Order on Improving the Nation's Cybersecurity

- NIST Secure Software Development Framework

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by the Better Scientific Software Fellowship Program, funded by the Exascale Computing Project (17-SC-20-SC), a collaborative effort of the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science and the National Nuclear Security Administration.

Author bio

William Hart is a 2022 BSSw Fellow and researcher in the Center for Computing Research at Sandia National Laboratories. He managed the Data Science and Optimization Applications portfolio for the US DOE Exascale Computing Project (ECP). He is an expert in computational operations research, and he has developed solutions for cybersecurity, critical infrastructure protection, engineering design, sensor data analysis, drug design, nuclear nonproliferation and remote sensing applications. Additionally, he has made seminal contributions to a variety of impactful open-source software libraries, including Pyomo (R&D100, INFORMS Computing Prize), Canary (R&D100), IDAES (R&D100), Dakota, and PEBBL.