Scientific applications are ever-growing in complexity: Interdisciplinary workflows in particular combine numerous methods and software components from different communities. Both software engineering concerns (e.g., embedding simulation software in CI/CD or performance analysis tools) and algorithmic concerns (e.g., performing optimization or uncertainty quantification on complex numerical models) drive these workflows.

Introduction

Each community has — for good reasons — typically preferred particular languages and tools, which are often incompatible. Further, many scientific software frameworks were designed as monoliths with no expectation of being embedded in higher-level applications. Thus, in order to facilitate complex scientific applications, we need to map abstract theoretical interfaces into equally universal software interfaces, enabling greater flexibility, reusability, and separation of concerns.

Case study: Simulating tsunamis

We wanted to perform Bayesian inference with uncertainty quantification (UQ) on a tsunami model, determining the tsunami source from buoy data. ExaHyPE served as the numerical model, while MUQ provided the UQ method.

Linking the two is straightforward on a theoretical level: MUQ's multilevel Markov chain Monte Carlo method needs only to iteratively pass parameter vectors to the tsunami model and receive some quantity of interest in return. Existing message-passing interface (MPI) support on both sides should allow for good scalability.

Monolithic application linking UQ algorithm and numerical model.

Monolithic application linking UQ algorithm and numerical model.

In practice, this interfacing turned out to be a challenge: In order to optimize algorithms and software, we often have to intentionally restrict the set of supported use cases.

In case of ExaHyPE, this meant focusing on a one-shot workflow where the user specifies the problem, and hardware-optimized, problem-specific code is generated and compiled. In addition, ExaHyPE builds on a fairly large number of dependencies and employs a somewhat unusual hybrid parallelization approach combining MPI with Intel's oneAPI Threading Building Blocks (TBB).

Taken together, these properties meant that it took us months to implement a scalable application linking MUQ and ExaHyPE. We had to dig deep into the parallelization of ExaHyPE for it to accept MPI sub-communicators from MUQ, modify its main routines to call it as a library, and rewrite parts of its custom build system. Along the way, we encountered a myriad of unexpected issues.

Microservices in scientific software

Linking MUQ and ExaHyPE was a painful experience, contrary to the theoretically simple link of the algorithms.

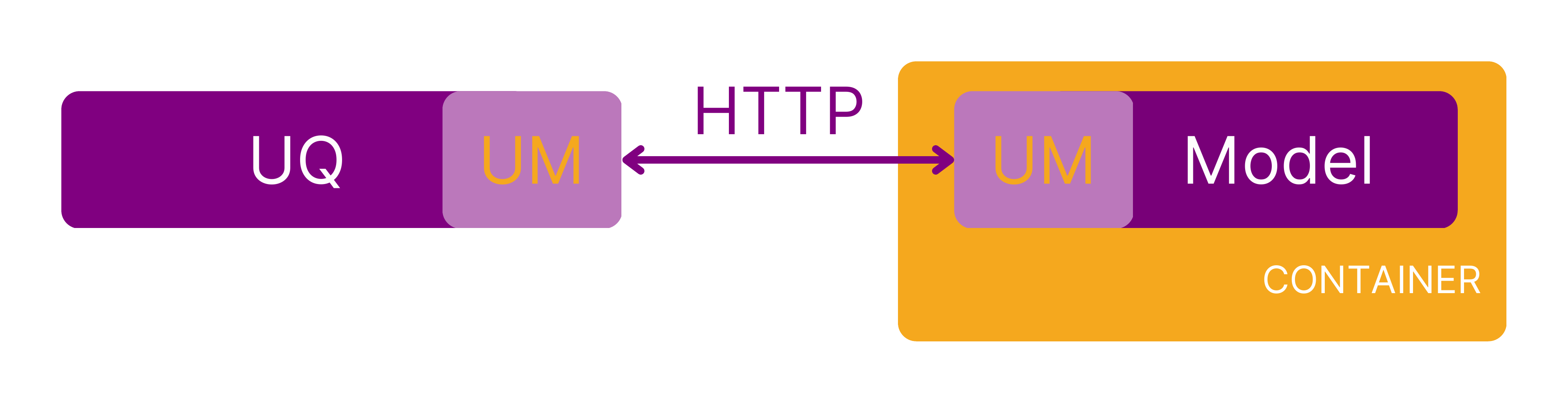

We, therefore, decided to try a completely different approach, taking inspiration from microservice architectures. Enter UM-Bridge, the UQ and Modeling Bridge: Instead of building one monolithic application encompassing UQ, numerical model, and HPC capabilities, we now separate each aspect into its own component. The UQ application requests evaluations through UM-Bridge, while the model application is now a server, launching simulation runs upon request. The model may run on a remote cluster, where a load balancer takes care of many parallelization aspects.

At its core, UM-Bridge is a simple network protocol based on HTTP and JSON, offering model evaluations and optional Jacobian and Hessian support. We provide a number of language-specific integrations that implement the protocol behind the scenes, allowing model calls or model definitions in terms of native function calls or objects. In addition, integrations specific to a number of UQ frameworks offer UM-Bridge clients fully embedded in the respective model interface. Adding UM-Bridge support to an existing project is therefore typically a matter of adding just a few lines of code.

The software now mirrors the abstract theoretical interface between UQ algorithm and model.

The software now mirrors the abstract theoretical interface between UQ algorithm and model.

Right away, UM-Bridge offers a number of benefits:

We can easily link tools that are written in different programming languages or are otherwise incompatible; all we need now is UM-Bridge support on either side.

UM-Bridge models can readily be containerized since the natural path to accessing a containerized application is via a network. Containerized models can be shared among collaborators, improving the separation of concerns between UQ and model experts. Containers also provide a high degree of reproducibility, which we used to build the first library of ready-to-run UQ benchmark problems.

Simple thread-parallel UQ codes are now enough to offload parallel model runs to a cluster, as distributing work across many model instances on the cluster is now up to UM-Bridge (specifically the Kubernetes setup we provide).

Rapid UQ application development: tsunamis revisited

We set out to revisit the tsunami problem using UM-Bridge. As before, we went with the ExaHyPE tsunami model. This time, we chose multilevel delayed acceptance (MLDA) as our UQ method. To spice things up, we wanted to build a Gaussian Process (GP) surrogate as the coarsest level in MLDA, replacing our less accurate hand-crafted coarse approximation. We used Google Cloud Platform (GCP) to provide the computational horsepower.

We had a clear separation of roles: Anne is the ExaHyPE expert, our collaborator Mikkel Lykkegaard is the developer of MLDA, and Linus has the most experience in cloud computing. UM-Bridge facilitated development at all stages:

- Only Anne had to perform the complex setup of the tsunami model and its dependencies, publishing the result as a container.

- Mikkel could immediately train a GP surrogate without deeper knowledge of the model, simply calling Anne's container through UM-Bridge.

- Meanwhile, Linus did performance testing on GCP, discovering an issue. Anne could fix the issue on her system, and updating the container was enough for everyone to receive the fixes.

- Linus spun up a large number of model container instances on a 2800-core cluster. Mikkel needed only to point his MLDA code to that cluster to offload costly simulation runs. The UM-Bridge kubernetes setup transparently took care of distributing work across all available resources on GCP, leaving the MLDA code completely oblivious of actually controlling many distributed model instances.

The new setup is arguably more complex than our previous attempt; still, we could complete this application in a matter of days instead of months!

Lessons learned and final thoughts

We believe UM-Bridge could be similarly beneficial when linking numerical models to optimization, machine learning, etc. The microservice-inspired approach certainly has limits, for example, when the numerical model is so fast to evaluate that network latency becomes dominant. In the many cases where UM-Bridge works, however, it has fundamentally changed how we develop UQ applications and collaborate with domain experts.

More broadly, scientific software is increasingly being used as a part of larger workflows but is not always being designed with that in mind. We believe that we have to move away from building large monolithic applications and, where possible, instead build smaller and more flexible components with language-independent interfaces.

Where to start

You can read more on UM-Bridge here:

- UM-Bridge release paper

- Preprint on large-scale applications with UM-Bridge

- UM-Bridge documentation and UQ benchmark library

We are actively expanding the UM-Bridge community, so send us an email if you are interested or need support!

Author bios

Anne Reinarz is an assistant professor of Computer Science at Durham University in the Scientific Computing Group. She is incoming Director of the Durham MSc in Scientific Computing and Data Analysis. She is enthusiastic about open-source, sustainable software. She was scientific coordinator of the ExaHyPE project and is one of the main contributors to the UM-Bridge project.

Linus Seelinger is a postdoctoral researcher at the Institute of Mathematics, Heidelberg University. His research is focused on uncertainty quantification with strong links to high-performance computing and numerical solvers of partial differential equations. He has contributed to the DUNE numerical framework, is a core developer of the MIT uncertainty quantification library, and, most recently, started the UM-Bridge project.